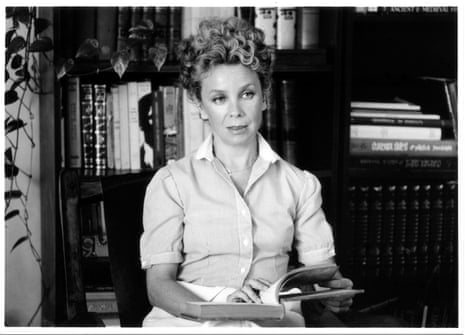

Tita Valencia’s first novel, Minotaur Fighting, was inspired by the end of a love affair.

Intimate, raw, and experimental, the 1976 book won Valencia the Xavier Villarrutia prize – the most prestigious award in Mexican literature. It also won her deep disapproval from the country’s male literati.

Valencia’s former lover was not named in the work, and even helped her with the edit. “He was fine with it … But all the others were outraged,” said Valencia. “They treated me so badly I decided I would never write anything personal again.”

After that, she rarely wrote again, focusing instead on her career as a concert pianist. And her novel, Minotauromaquia, fell off Mexico’s literary radar.

Now it is being reprinted by the National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM, as part of a new imprint highlighting works by Latin American women who were once feted but have fallen out of print.

Books in the series have been selected by a committee of younger female writers, and the first five, written by four Mexicans and an Argentinian, were launched at the Guadalajara international book fair at the start of December.

“The Vindictas collection was born out of deep indignation,” said Socorro Venegas, the head of the project, who said it has introduced her to works of “great literary value” she never knew existed. “It is women writers exhuming other women writers.”

The oldest book in the collection is The Place Where The Grass Grows, by Luisa Josefina Hernández, which was published in 1957. It tells the tale of a woman confined to the house of a stranger and explores how over-protective men leave the protagonist feeling annulled.

In contrast, the woman at the centre of another of the novels is rich and powerful, never gets physically old, and has countless lovers. De Ausencia, or About Ausencia, was written in 1974 by a well-known journalist called María Luisa Mendoza – yet she too never won recognition as an author.

“I never got the literary place I deserved,” Mendoza said in one of the last interviews she gave before she died last year at the age of 88.

In her forward to another book in the series – In State of Remembering by Tununa Mercado – the writer Nora de la Cruz describes how she fell in love with the author’s work after reading one short story.

“I spent years after that looking for more,” De la Cruz writes. “It was impossible: her books were not in bookshops or libraries, just a few fragments on the web.”

Marcela del Rio’s novel El Cripto del Espejo, or The Mirror’s Crypt, emerged from the events she observed as Mexico’s cultural attaché in Prague in the 1970s. The book was well received when it was published in 1988, but it too was soon forgotten.

“There was a lot of injustice when it came to recognizing the value of work written by women – especially when it came to studying it,” Del Rio said. She added that literature students she taught had regularly wanted to write about her work, but were told by faculty heads to focus on established male writers instead.

Nevertheless, Del Rio said that the previous generations of women writers had it much worse.

Her own mother wrote several novels in the 1930s, but only published one. She managed this because her husband used his connections to get a meeting with Mexico’s education minister who liked the book.

“Getting published back then mostly still depended on being associated with a man who had a certain influence,” the 87-year-old said.

A friend of Del Rio’s mother called Asunción Izquierdo, was married to an important politician but he was so opposed to her writing he once threw her typewriter out of the window.

Nevertheless, she persisted: writing in secret and using a number of different pseudonyms, Izquierdo published two books of poetry and eight novels between the 1930s and 1960s.

Izquierdo died alongside her husband in 1978, when the couple were murdered in their home. Their grandson was convicted of the crime but always insisted on his innocence.

Now the Vindictas Collection is trying to find out who to ask permission to publish Izquierdo’s first novel, Andréïda: the Third Sex. Similar problems have also arisen with other writers who died without bequeathing the rights to their work to anybody, suggesting that the disdain of the literary establishment had rubbed off on them.

But more than four decades after she decided that publishing Minotauromaquía had been more trouble than it was worth, 81-year-old Tita Valencia said she is delighted to see the book in print again.

“This is very important to me,” she said.

This article was amended on 2 January 2020 to correct that Minotaur Fighting was not Tita Valencia’s last novel.