First American Women Inventors

Before the 1970s, the topic of women’s history was largely ignored by the general public. Women have probably been inventing since the dawn of time without recognition. Many women faced prejudice and ridicule when they sought help from men to implement their ideas. Property laws also made it difficult for women to acquire patents for their inventions. By 1850 only thirty-two patents had been issued to women.

Image: Sybilla Masters Corn Refiner

Sybilla Masters (1715)

Sybilla Masters invented a way to clean and refine the Indian corn that the colonists grew in early America and received the first patent issued to man or woman in recorded American history in 1715. Masters’ innovation processed the corn into many different food and cloth products.

While it was acknowledged that Sybilla Masters [link] had created her invention – Cleansing Curing and Refining of Indian Corn Growing in the Plantations – but according to the laws at the time, women could not own property, not even intellectual property. Therefore, Sybilla’s patent was issued in her husband’s name in 1715.

The following excerpt is from an 1891 Scientific American magazine article that discusses the patent issued to Sybilla Masters, but the language is offensive:

It is granted by King George the 1st, and the official entry in Roman text is as follows: “Letters patent to Thomas Masters, of Pennsylvania, Planter, his Execrs., Amrs. and Assignees, of the sole Use and Benefit of ‘A new Invention found out by Sybilla, his wife, for cleaning and curing the Indian Corn, growing in the several Colonies of America, within England, Wales, and Town of Berwick upon Tweed, and the Colonies of America.'”

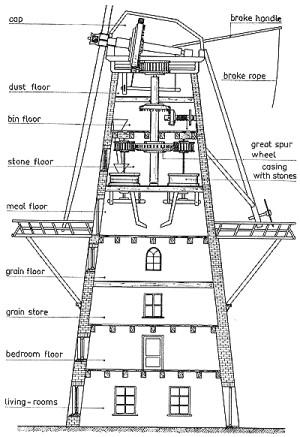

The two upper illustrations [refers to patent drawing] show the cleaning and the lower the curing. The top view represents the sheller, worked by animal power, probably a donkey (Asinus vulgaris). The gearing and shaft are of wood, and a reciprocating motion is produced by a series of detents upon a revolving cylinder something after the manner of a musical box.

It is to be feared that Dame Sybilla’s invention did not attain to as wide a field of application as was covered by the letters patent. It is more than probable that the obtuse agriculturist continued to shell corn sitting on a pine plank with a spade edge to scrape them off by, in spite of the “paines and industrie” of the dame.

Thomas Masters purchased Governor’s Mill for his wife Sybilla’s business venture – cleaning and curing Indian corn into what she called ‘Tuscarora Rice.’ He later received a second patent for another of Sybilla’s inventions, entitled “Working and Weaving in a New Method, Palmetta Chip and Straw for Hats and Bonnets and other Improvements of that Ware.”

Hannah Wilkinson Slater (1793)

Hannah Slater’s invention was for a method of producing sewing thread from cotton. This invention was likely inspired by the mills run by her husband, Samuel Slater, a native of Derbyshire, England. In his youth, Samuel excelled in mathematics and demonstrated exceptional skills as a mechanic. He served an apprenticeship in an English spinning mill and had learned to operate all the machinery involved in converting raw cotton into yarn before coming to America in 1789 when he was 21 years old.

Within a few days of his arrival in New York City, Slater was hired by the New York Manufacturing Company, but the mill was poorly equipped and lacked access to enough water to provide the necessary power for operating spinning machines. Slater learned that the firm of Almy and Brown operated a spinning mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island and wrote to Moses Brown, who had provided most of the capital for building the mill. Brown hired Slater immediately.

Slater’s principal responsibility was to design and construct duplicate models of the equipment used in British milling establishments. Brown again supplied the capital. With the aid of a local woodworker, an iron manufacturer, and a general helper, Slater constructed the first practical copies of English carders, water-frame spinners, and looms in the United States. The new mill went into operation in December 1790 and became the first successful water-powered cotton mill in the United States. Slater soon became a partner in the firm.

Slater began with the English system of hiring women and children from distant homes and trained them to operate the machinery, but New England families bristled at being separated. Therefore, he created a system of tenant farms around his mills, moved whole families in, and provided work for everyone. The raw cotton was sent out to local women for cleaning before it came to the mill for carding.

Soon after the mill went into operation, Hannah Wilkinson, daughter of Moses Brown’s business partner, married Samuel Slater. In 1793, only four years after Samuel Slater began his work, Hannah Slater filed for a patent for her method of making cotton sewing thread to the Patent Office created by the Patent Act of 1793.

Mary Kies (1809)

The Patent Act of 1790 opened the door for anyone, male or female, to protect his or her invention with a patent. However, in many states women could not legally own property; therefore, many women did not bother to patent their inventions. On May 5, 1809, Connecticut native Mary Kies [link] received the first U.S. patent issued to a woman for her method of weaving straw with silk. Using her new method, Kies made and sold beautiful women’s hats. First Lady Dolley Madison [link] publicly thanked Kies for boosting the nation’s hat industry.

Straw bonnets manufactured in Massachusetts alone in 1810 had an estimated value of more than $500,000, a tidy sum for the time. New England’s hat industry was one of the few industries that continued to prosper during the War of 1812. Mary Kies was unsuccessful in her attempts to profit from her invention, however. Samples of the straw fabric covered by her patent and woven by Mary Kies are on display at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut.

Tabitha Babbitt (1810)

Tabitha Babbitt was a member of the Shakers at the Harvard Shaker community in Massachusetts. One day as she spun her goods she observed two men at the nearby sawmill, who were sawing logs with the difficult two-man whipsaw, pulling it back and forth. Realizing that a round blade would be more efficient, Babbitt invented the first circular saw blade, a round metal disc with sharp teeth on the edges.

Babbitt had a prototype made and attached the blade to the axle of her weaving machine at a high rate of speed, proving her invention a success. The saw blade easily cut wood and other materials. A larger version of her design was first used in a sawmill in 1813, where it was mounted on a table and hooked up to a water-powered machine to reduce the effort to cut lumber. Her basic design was used at various American saw mills.

As with so many inventions, numerous people claimed that they independently invented similar devices around the same period in various parts of the world. Due to her beliefs as a Shaker, she did not patent her design, instead sharing it freely; therefore, it could be used by others. Two Frenchmen patented Babbitt’s invention in the United States three years later when they learned about it in Shaker newspapers.

This is an excerpt from a Bowdoin College publication entitled The Democratizion of Invention, Chapter 5: ‘Women Inventors’:

Only 77 patents were credited to women from 1790 through 1860, even though 4773 patents were issued to male patentees in 1860 alone. The lower level of female inventiveness relative to men … persisted throughout the period. … The post-Civil War contribution of women inventors amounted to less than 1 percent of all patents granted by the United States Patent Office. However, the growth rate of women’s patents exhibited a strong upward trend that exceeded that for male patentees. In the centennial year of 1876, the cumulative total patents for women amounted to just over 1000, whereas by the 1890s the number of patents issued to women was double that of the preceding decade. …

Several factors were likely responsible for the rapid growth in the numbers of women participating in patenting over the period, including their higher labor market participation, greater access to education over time, and legal reforms that improved women’s economic rights.

Judy Reed (1884)

In January of 1884, Judy Reed of Washington DC applied for a patent for her ‘Dough Kneader and Roller,’ an improvement to existing dough kneaders. Reed’s device allowed the dough to mix more evenly as it progressed through two intermeshed rollers carved with corrugated slats that would act as kneaders. The dough then passed into a covered receptacle to protect the dough from dust and other particles in the air.

Note that only Reed’s initials appear on the patent: J.W. Reed

Many early women inventors used their initials to hide their gender, and patent applications did not require them to reveal their race. Therefore, it is unknown if there are earlier African American women inventors before Reed.

On September 23, 1884, Reed received Patent No. 305,474 for her bread kneader. There is no record of her life beyond this event, but she is considered to be the first African American woman to receive a United States patent.

Suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage wrote in 1883:

It is scarcely thirty years since the first state protected a married woman in the use of her own brain property. Under these conditions, legally incapable of holding property … that woman has not been an inventor to an equal extent with man is not so much a subject of surprise as that she should have invented at all.

While every invention, however small, develops new industries, provides work for a multitude of people, increases commercial activity, adds to the revenues of the world, and renders life more desirable, great inventions broaden the boundaries of human thought, bring about social, religious and political changes, hurrying mankind on to a new civilization. … No less is the darkness of the world kept more dense, and its civilization retarded, by all forms of thought, customs of society, or systems of law which prevent the full development and exercise of woman’s inventive powers.

Patents Issued to Women

United States law defines a patent is a right granted to the inventor of a (1) process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter, (2) that is new, useful, and non-obvious. A patent is the right to exclude others from using a new technology. Specifically, it is the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, importing, inducing others to infringe, and/or offering a product specially adapted for practice of the patent.

Patent law is designed to encourage inventors to disclose their new technology to the world by offering the incentive of a limited-time monopoly on the technology. This limited-time term is 20 years from the earliest patent application filing date. After the patent term expires, the new technology enters the public domain and is free for anyone to use.

By 1840, only twenty more patents had been issued to women, all related to apparel, tools, cookstoves, and fireplaces. From 1855 to 1865, women received an average of 10.1 patents per year while their male counterparts received 3,767.4 patents. During the next decade, 1865 to 1875, the number of patents issued to women increased to 67.3 compared to men’s 11,918.4 patents.

Nineteenth-century social reformer Ida Tarbell said this about women and patents:

No improvement which a woman can originate will be slighted because it comes from the hand of a woman. It only remains for her to take full possession of a field in which there is abundant opportunity for her to win great successes and do great good.

Today hundreds of thousands of women apply for and receive U.S. patents every year, with more than 12 percent of all patent applications coming from women inventors.

SOURCES

About.com: Sybilla Masters

Encyclopedia.com: Samuel Slater

The Circular Saw and a Shaker Woman

Bowdoin College: Women Inventors – PDF

Futurist Speaker: A Study of Women Inventors

5 Female Inventors Who Changed Life As We Know It

Colors of Innovation: Early History of African American Inventors

Hello,

The title of this article “First American Women Inventors” had me thinking the article would be talking about Native American women inventors. Seems a little problematic, doesn’t it, that the article is about White women, when Indigenous women had been in the Americas inventing things for 10,000 years? Almost like the Native women don’t count? Almost like Native history didn’t exist? Simple fix to not look racist!

Be the advent of change, rather than a heckler. make your own article, then link it here.