Over the past decade, the women’s magazine has undergone a radical makeover. While 00s glossies consisted largely of insidious bodyshaming and bankrupting shoe recommendations, in recent years female-centric journalism has migrated online, simultaneously shifting its gaze to social justice, mental health and the hitherto hidden realities of womanhood. It has not always been a smooth transition: last week, the online women’s magazine the Debrief announced its closure, with its parent company, Bauer Media, deciding to refocus resources into its print product Grazia. Last year, Sarah Millican’s Standard Issue shut, while US website the Hairpin followed suit in January. Yet a host of other publications remain committed to doing things differently. Here, the women behind London-based site gal-dem and Mille World, an online magazine aimed at Arab readers, explain why they are determined to reimagine the women’s magazine as a force for positive change. RA

Mille World

Sofia Guellaty launched Mille World out of frustration that it did not already exist. She was looking for a publication that engaged with what it meant to be a young Arab woman. Versace, Dior, Calvin Klein and Chanel were sending hijabs down their runways, but who was catering to the savvy, cosmopolitan Arab women looking to reclaim the Arab narrative for an educated Arab audience? It turned out no one was, so Guellaty decided to.

Educated in Paris, but born and now based in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, 35-year-old Guellaty was at the helm of Condé Nast’s first Middle East launch, the now-closed Style.com/Arabia, in 2012. “I kept hearing about things being ‘good enough’ for the Arab market. That really got to me, this ‘good enough’ attitude. Two things: one, it’s not good enough, what you’re doing is crap. Two, it’s racist,” Guellaty says. Two years ago, she quit Condé Nast; last May she became pregnant with her first child. It was during her pregnancy that she developed the idea for Mille World. After giving birth, she recruited the first members of the board, which now includes Saudi princess Reema bint Bandar al-Saud and Saif Mahdhi, the president of Next Models. She recruited the company’s CEO, Nez Gebreel, from the Dubai Design and Fashion Council. It was crucial to Guellaty that her executive and editorial team were Arabs and leaders in their field.

“Because of colonisation – whether it’s real, as with Tunisia and France, Egypt and the UK, or whether it’s cultural supremacy – [Arab readers] tend to be like: ‘If a white guy did it, it must be good.’ I wanted to change that. I wanted the whole team to be Arab, which never happens. At the big fashion titles, like Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, there’s not one Arab there – maybe there’s an Arab assistant,” she says. “They write articles about ‘Oriental fashion’ being on the rise. We write about decolonising beauty standards. We’re very now. They’re very yesterday.”

Mille World launched in January and already has 40,000 unique visitors a month. Its readers come from across the Arab world and diaspora, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Lebanon, Egypt, France, the UK and the US. Its 12-person editorial staff is equally international, based in Dubai, London, Paris and Tunis. The deputy editor, Samira Larouci, 28, has lived in Dalston, London, for years, but she was raised in “very, very white” Chichester by her Moroccan parents. She left i-D magazine in July, having helped set up its luxury lifestyle site, Amuse. She was put in touch with Guellaty by a mutual friend. Their first phone call lasted two and a half hours. “We were talking about Arab identity issues; I’ve always been seeking a community of my own to connect with. We both agreed there was a voice missing that we wanted to hear. It was young, inclusive and not based around materialism,” Larouci says. “We wanted to address that need. It’s almost laughable no one’s done it before.”

Larouci now commissions and edits the bulk of the site’s editorial content – 60 pieces a month, every one of which is translated into English, French and Arabic. She is interested particularly in Arab counterculture and championing Arab artists who do not have any other platform in their region. “The reader I want to reach is someone studying in Washington, raised in Saudi, who’s in a sort of cultural limbo. That’s where I come from. I want to find those people in LA who are interested in feminism in the Arab world,” Larouci says.

All this is only financially possible thanks to Mille World’s consultancy wing, led by co-founder Myriam Djelouat, which translates its connection with the Arab market into campaign advice for massive brands such as LVMH, Ralph Lauren and Converse. As Mille World’s promotional material points out, 40% of people living in the Arab world are millennials with higher spending power than their peers everywhere else, including in the US.

“Our generation is the highest-spending generation in history, but it’s also woke. [The big brands] are realising they need to rethink,” Guellaty says. “Mille World is my playground and I’ll write what I want there. If this Gucci bag sucks, it sucks and it’ll never see the light of day on my website. But if you want help on a Gucci campaign? Yeah, for sure,” she says. “What I want is a generation-defining media, something like what Jefferson Hack did with Dazed and Another Magazine. It’s like, here is a media through which I can understand the world I’m in, something that inspires me within my own identity.” PG

gal-dem

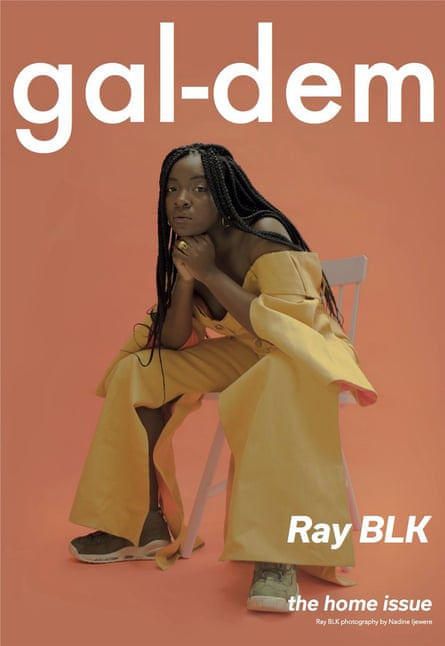

Deep in the belly of a south London car park lie the offices of gal-dem, an online magazine produced exclusively by women and non-binary people of colour. It is not big – each of the work studios in Peckham Levels has been converted from a single parking space – but it is significant. By parsing culture and current affairs through a prism of intersectional feminism, covering topics from Grenfell to mooncups, gal-dem is one of the publications changing the face of female-focused media.

Liv Little was halfway through a politics and sociology degree at the University of Bristol when she founded gal-dem and the site’s ethos sprang directly from her studies. “The issues that I was really interested in politically were the specific, nuanced ways that women are affected by legislation in this country,” she says. “So I did a lot of campaigning and research around women seeking asylum in the UK and Yarl’s Wood [immigration centre] and how types of violence which they would fall victim to were gendered.” In doing so, Little observed “a lack of understanding of a different type of experience” faced by women – especially women of colour – and a gap in the market for a site that could tell their stories.

As a concept, gal-dem is a world away from the blinkered women’s glossies available to the editorial team in their youth. While those magazines shared some women’s stories, the scope was narrow, and much of the content was designed to reaffirm strict beauty standards. gal-dem, meanwhile, has no such agenda, aiming to provide women with just one thing: a voice. In this sense, the site is part of a much broader cultural shift in women’s media – one that has seen print titles fail (recent casualties include Company, She, Glamour, Bliss and Sugar) and a new breed of online magazine take their place. Riding the fourth wave of feminism, publications such as The Pool and Refinery 29 are fuelled not by materialism, but by a rich seam of untapped subject matter: the experiences women have long been told to keep quiet.

While the gal-dem team acknowledge their position in the wider landscape of newly feminist media, they are careful to distinguish themselves from their peers. “There is a tendency within feminism for its face to be quite white and middle-class,” says Little. “To see an editorial team comprising women of colour is a rarity; I think that is clearly our point of difference.” From her desk in the gal-dem offices, the deputy editor – and Guardian contributor – Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff explains how the focus on issues that affect women of colour manifests itself in gal-dem’s attitude. “The tone in general is a bit more serious than the Refinerys and Bustles; we don’t have that ‘you’re talking to your best friend’ thing going on,” she says. “The nature of the topics we’re talking about a lot of the time don’t really lend themselves to that and we don’t want to ever dilute that seriousness.”

Slowly, gal-dem’s efforts to rectify a lack of representation are being echoed by the mainstream media – with decidedly mixed results. Since he took over six months ago, the Vogue editor Edward Enninful has managed to include five women of colour on his covers (February’s Vogue featured Little in a spread about “the new suffragettes”), yet glossies are still regularly derided for their treatment of black women. In November, the actor Lupita Nyong’o expressed her disappointment at Grazia’s decision to photoshop away her natural hair on its cover; the previous month, the Evening Standard’s magazine caused much consternation by airbrushing Solange’s braids. And just because online magazines tend to avoid scandal, that does not mean they are necessarily much better, Brinkhurst-Cuff says. “It would be more hidden if there was an issue online, because you don’t have the physical print cover to see. We can say Alexandra Shulman only published 12 black women on the cover, whereas if an online publication is pretty much exclusively publishing white writers or using stock images of white women you’re arguably less likely to pick up on that.” That said, she sees the new online media “struggling towards intersectionality, for the right or wrong reasons. Diversity is in fashion right now, but we hope it’s not always about money.”

Money, however, is something gal-dem is beginning to consider seriously. Until now, it has been a voluntary organisation. Nobody gets paid, apart from contributors on specific brand collaborations; the annual print issue, the covers of which hang from the office’s chipboard walls, is more passion project than money-maker. But as the site has grown – gal-dem receives “anything from 4,000 to 20,000 unique visitors a day”, according to Little – the team believe it is turning into an economically viable enterprise. Little has just stopped working full-time and the team are developing a business plan.

It is still early days for the new breed of women’s magazine and the economic forecast remains uncertain – but, in terms of broadening the scope for women’s media, the legacy of gal-dem and its peers already seems indelible. RA

Four more new-wave websites

The Pool

Aimed at the time-stretched woman, this online magazine from Lauren Laverne and former Red editor Sam Baker focuses on snackable content – its intimate personal essays and practical advice are all stamped with an average reading time.

Man Repeller

Initially a blog documenting Leandra Medine’s love of ugly and offbeat fashion, Man Repeller now also publishes smart, funny and moving pieces on everything from ghosting to antidepressants.

Broadly

“For women who know their place” runs the tagline to Vice’s women-focused channel, which covers feminist issues with an emphasis on reportage.

Burnt Roti

On Londoner Sharan Dhaliwal’s lifestyle site, writers of south Asian heritage discuss topics including bereavement and menstruation.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion